|

|

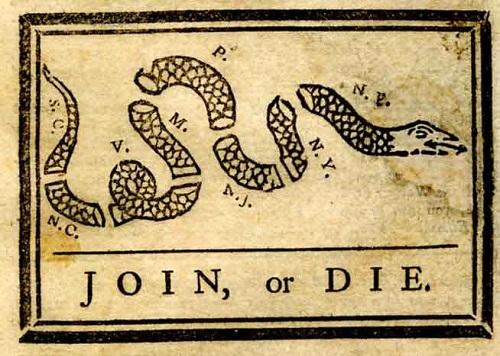

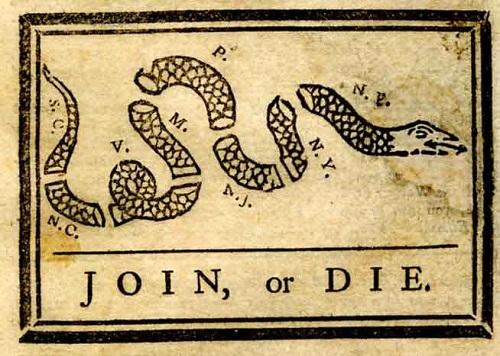

RESISTANCE & REVOLUTION ARTWORK Featured below are five famous pieces of artwork depicting critical junctures in the American revolutionary saga. Over the short period of three decades, Great Britian's thirteen North American colonies transitioned from relative satisfaction as members of the mighty British Empire through a period of general discord and staunch resistance culminating in revolution-brought independence. The images are positioned chronologically. They tell one version of the story, as do most renditions of history offered through artistic mechanisms, thus underscoring the broader lesson for those who study history that artists and historians are not good friends. |

|

|

The drawing above appeared in Benjamin Franklin's Philadelphia Gazette on May 9, 1754. Contrary to popular thought, the sketch was not created to urge united colonial effort against tyrannical Great Britain, although certainly the message is fully applicable to the Revolutionary War. Instead, Franklin presented this illustration at the Albany Conference in response to the colonies (at the moment, happy to be an extension of the mother country) facing serious trouble with France. Open warfare commenced—the French and Indian War. Like the three previous Colonial Wars, this conflict had a European version (Seven Years War). Unlike the Colonial Wars before it, the French and Indian War was critical to United States history because in effect, Britain and France warred for supremacy on the North American continent. The British victory immediately and drastically changed the relationship between the mother country and her thirteen colonies. Hence, the event of the French and Indian War and its dates, 1754 through 1763, are as important to learning United States history as any subsequent events and dates, even though the United States was yet to be conceived—or even imagined. "JOIN, or DIE." represents two firsts in American history. It is the earliest known legitimate appeal for political unification of the colonies to accomplish an objective thought too difficult for divided and uncoordinated efforts of colonies acting alone (or with just one or two partners). The snake is segmented into eight labeled parts representing twelve of the thirteen colonies which will soon enough revolt against Britain—four colonies were grouped into the New England region and Delaware was part of Pennsylvania at the time; Georgia was ignored. Franklin's piece is generally considered to be the first American editorial cartoon. It contains every ingredient that a perfect political cartoon encapsulates—a clear statement of opinion conveyed by simple artwork with little, if any, adornment; minimal verbiage (if at all) that serves to bolster the picture's intent. The resulting message is crystal clear (whether or not the viewer agrees is, of course, irrelevant). |

|

|

Thanks to this contrived engraving by Paul Revere, the Boston Massacre is commonly interpreted as tyranny and brutality on the part of Great Britain toward the colonies. The familiar story is straightforward—a contingent of British Redcoats were marched to a busy area of Boston and, upon command, fired into the crowd, killing five innocent civilians. Actually, there's more to the story than that. In truth, a squad of Redcoats was cornered by an angry mob. Far outnumbered (initially, hundreds of Bostonians assembled at King Street on March 5, 1770), and certainly fearful of severe bodily harm if not death, the soldiers discharged their weapons into the threatening mob. The confused action resulted in murder charges against all nine soldiers. Serving as defense attorney was John Adams (yes, that's correct); there were two convictions. The guilty soldiers were branded on the thumbs and then released. A monument to one of the Bostonians killed, Crispus Attucks, now stands on Boston Common. Coupled with a highly propagandized account of the incident by Samuel Adams, Revere's picture nourished the idea that the Redcoats were a band of ruthless soldiers willing to expand their government's tyranny over the colonists. Revere altered the real incident in numerous ways. First off, his painting gave no clue of the details leading up to the bloody episode. Firstly, Boston was the absolute hotbed of ever-growing colonial resistance to the Crown's policies. Also, the "massacre" was precipitated by a brawl between local roughhousers and off-duty Redcoats, both groups more interested in landing a punch than . Moreover, government officials warned the throng of protestors, in proper legal fashion, to disperse or face whatever action may arise when inflamed public emotion meets necessary government authority. Revere's local participants, joined by a cute tail-wagging puppy, look more like they are enjoying the fresh air and bright sun of an early spring day in New England. No doubt some are even considering a picnic later! No rocks, no ice chunks, no clubs are to be seen. The diabolical soldiers, on the other hand, have marched to the area to shoot, firing-squad style, into the peace-loving assemblage of citizenry. Really? Coincidentally, this event brings to the historical forefront two of Boston's most extremist resistance leaders in Revere and Adams. Both will participate in the Boston Tea Party (more criminal than patriotic, but that's another story) in December of 1773. Can you identify the tragic incident, occurring almost two centuries to the month later, when another chaotic confrontation between government militia and angry demonstrators resulted in a handful of civilian casualites by indiscriminate shooting. |

|

|

The Second Continental Congress, forced to deal with worsening relations between the thirteen colonies and Great Britain (leading to bloodshed at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill in the spring of 1775), will form a committee charged with preparing a formal declaration of independence from Britain. The five committee members were John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Robert Livingston of New York, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. John Trumbull's "Declaration of Independence" appeared in Harper's Weekly on July 3, 1858. It is the most popular of several Trumbull paintings of the American revolutionary movement. The five men are portrayed presenting their committee work to Congress as membership stands forthrightly in support. Actually, no grandiose presentation ever occurred. Trumbull's skillful composition cleverly "ranks" the five contributors to the Declaration of Independence. The principal author was Thomas Jefferson, only 33 years old at the time. His authorship of the Declaration underscores his reputation as one of the most eloquent writers among all the Presidents who will in American history. Curiously, he was a compromise member of the committee, appointed to appease the South! Appropriately, Jefferson is shown, front-and-center wearing a red vest, presenting the document to Congress. Trumbull has placed Jefferson at the unavoidable viewer focal point of the painting. He is flanked by Adams and Franklin (some viewers claim to see Jefferson standing on Adams's foot). Decidedly behind the trio of Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin are Livingston and Sherman. (Incidentally, this is the Jefferson that sculptor Gutzon Borglum will choose to place on Mount Rushmore along with three other Presidents carved as Presidents.) Trumbull's historical moment was followed by a ceremonious signing, John Hancock first and ostentatious, as president of the Continental Congress, then each member depicted in Trumbullís painting solemnly affixing his name to the Declaration, right? No. Most of the delegates did not sign the document until August 2! The image accompanies Jefferson on the two-dollar bill. |

|

|

The familiar painting above is the work of Emanuel Leutze. It depicts General George Washington leading his force of Continental soldiers across the Delaware River to attack Hessian troops encamped at Trenton, New Jersey. The episode occurred on Christmas night in 1776. The sneaky advance (ten miles overland after the river crossing) resulted in America's first major victory of the Revolutionary War. In fact, the Hessians were so taken by surprise that most were captured. This despite the fact that Washington's approach was detected by Loyalist operatives. By one version of the story, the Hessian commander, Colonel Johann Rall, was too busy drinking and playing cards with some of his subordinate officers in the comfort of a warm fire to bother reading a note, handed to him by a messenger, warning of the oncoming enemy force. It was in Rall's breast pocket, unread still when he was mortally wounded by American soldiers who raided his headquarters! Leutze's painting contains several factual flaws. Although appropriately symbolic of Washington's leadership, the general would certainly not have been standing as he is—that would have been simply stupid. For sure, the appearance of the American flag (held by Lieutenant James Monroe, future President) is fabricated because, for one thing, the design Leutze shows had not yet been adopted by Congress. And what's the point of displaying the flag when fording the river in the dark of night for a sneak attack? Incidentally, at the time of the crossing, Washington's army included others who later become notable Americans, such as Alexander Hamilton (Secretary of the Treasury) and John Marshall (Chief Justice). So, why does Monroe, and not Hamilton or Marshall, get to be in Leutze's painting? It is highly doubtful the boat was so crowded that it seems to be just one passenger's slight body shift away from capsizing! But perhaps Leutze is one artist who has a legitimate excuse for his work's exaggerations. His purpose was not to show American history for history of America's sake, but instead to inspire liberals in his native Germany to revolt against the incumbent government there in 1851. Knowing Leutze's heritage explains another of the painting's distortions. The river is modeled after the Rhine (Washington Crossing the Rhine?), where ice tends to form in jagged chunks as pictured, not in broad sheets as is more common on the Delaware. Leutze completed at least three of these paintings. The very original was destroyed during World War II. Two still exist—one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City; the other in the West Wing reception area of the White House. The painting is the image selected by New Jersey to appear on its state quarter. |

|

|

The Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783, and ratified by Congress the following April. Under its terms, Great Britain acknowledged sovereignty and independence of the United States and relinquished all territory in North America south of Canada (not so simple, actually, but first-President George Washington's administration would tie up loose ends). Congress, then operating under the Articles of Confederation, appointed John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens, and Thomas Jefferson (shown left to right in the painting) to conduct peace talks. As it turned out, Franklin and Jay emerged as the principal negotiators, and only those two plus Adams would actually sign the treaty on behalf of the United States because neither Laurens or Jefferson ever made it to Europe to take part. Benjamin West's painting of the event is unique in that the finished work is unfinished. The two British negotiators, David Hartley and Richard Oswald, refused to have themselves immortalized in such a hugely embarrassing moment in British Empire annals. The work is interesting also because Jefferson does not appear. West replaced him with young William Temple Franklin (Benjamin's grandson), who served as secretary for the American treaty delegation. Temple's father (and therefore, Benjamin's son) was Governor of New Jersey and a prominent Loyalist during the American Revolution, especially noted for his strong support of the Stamp Act. (Oddly, doesn't Temple strongly resemble Jefferson? And, doesn't the painting, though positioning and facial expression, make Temple appear to be the dominant instead of auxiliary team member?) Thanks to Adams, the painting survives today. When Adams returned to the United States, he took the picture to hang in his home. (Did he consider it a sort of best-available souvenir image to remember the event, much like we today might think of taking an impromptu photograph or buying a post card or grabbing a hotel pen?) |