|

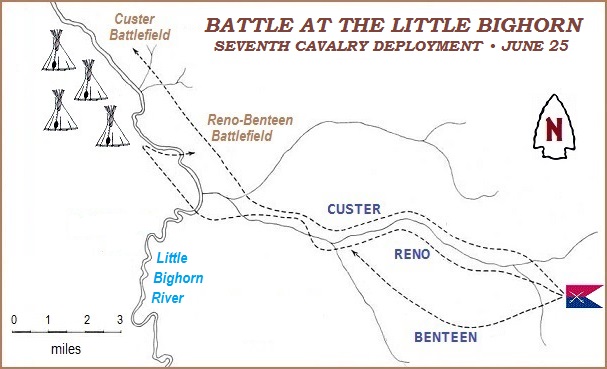

In the early 1860s, disillusioned with the reservation policy of the Great White Father, angry Indians inhabiting the North American Plains took to the warpath. Some Indians resisted outright any limits to their hunting grounds. Other tribes, willing to accept the government's boundaries, felt betrayed whenever whites infringed on designated Indian lands to prospect for gold, lay railroad track, fence homesteads, or slaughter buffalo by the hundreds. A series of bloody engagements ensued between Indians and bluecoats throughout the West over the next three decades. The event most readily associated with the Plains Indian Wars took place in June of 1876 when Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer's 7th Cavalry was defeated by a massive Indian force at the Little Bighorn River in southeastern Montana. There is as much myth surrounding Custer, and his ill-fated "Last Stand" in particular, as any topic in American history. Fierce Sioux resistance spearheaded by Chief Red Cloud in the Powder River region of northern Wyoming Territory caused the government to seek negotiation in 1868. The resulting Fort Laramie Treaty called for the United States to abandon its guardian forts along the Bozeman Trail, awarded to the Sioux all of present-day South Dakota west of the Missouri River, and allowed the Indians to continue hunting buffalo within the "unceded territory" stretching from the western boundary of the Black Hills to the summit of the Bighorn Mountains. Essentially, the Sioux could choose to live on the Great Sioux Reservation and draw provisions from the government, or roam freely throughout the Powder River Basin to hunt wild game. Either way, there was to be no significant interference from whites. In lieu of chasing buffalo, the reservation Indians were promised oxen, plows, wagons, and other farming necessities. Education for Indian children up to 16 years of age was also provided. Within a half dozen years, both treaty parties would commit acts in violation of the Fort Laramie accord. Red Cloud and Spotted Tail led some 15,000 Sioux to the reservation. A smaller group of about 3,000, Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull among them, continued to resist all ties to the United States government and remained in the unceded country. (About 400 Northern Cheyennes mingled there, as well.) Sitting Bull chastised his Sioux brethren who succumbed to the lure of free rations offered on the reservation: "You are fools to make yourselves slaves to a piece of fat bacon, some hard-tack, and a little sugar and coffee." The fact is that practically all the Sioux spent some amount of time on the reservation because the treaty itself tacitly encouraged a constant flow of Indians between the abundant unceded country, where the free life of the buffalo hunt could be enjoyed during the summer, and the Great Sioux Reservation, offering the security of free agency rations throughout the harsh winter months. The Indians who shuffled back and forth between reservation and unceded territory were difficult for the government to manage. In addition, their movement provided excellent opportunities to conduct periphery raids against settlers near the fringes of Indian land and to harass the railroads (the Indians had pledged in the Fort Laramie Treaty to permit the iron horse to pass unmolested through their lands). The Sioux typically defended these violations by claiming that the treaty had not been properly explained to them. During the summer of 1874, Custer was assigned to lead an enormous expedition through the Black Hills. Its dual purpose was to determine a suitable location for a military fort (to better supervise the Indians) and settle the question of gold in the Hills. The expedition's discovery of gold there made whites immediately covetous of the region. Once geological survey parties sent into the Hills confirmed the presence of gold, one newspaper editorial after another clamored for settlement. Army patrols made half-hearted efforts to keep prospectors out, but the reality of the situation was that it was just a matter of time before the government would bow to the influx of settlers. In 1875, the United States began to apply pressure on the Indians to sell the Black Hills. A commission traveled from Washington to meet with the Sioux and discuss terms of sale. The Indians balked at the government's offer of $6 million and negotiations ceased. Frustrated, President Ulysses S. Grant decided that since it was primarily the hostiles of the unceded territory who were standing in the way of a deal, the obvious solution was to clear them from the region. Acting on orders from the War Department, General Alfred Terry departed in mid-May of 1876 from Fort Abraham Lincoln in northern Dakota Territory and headed toward defiant Sioux and Cheyenne Indians assembling in the Powder River region. With Terry was Custer, in command of the 7th Cavalry. Custer has been unjustly characterized regarding his conduct and attitude toward the Indians. Noted historian Robert Utley concludes that given today's era of heightened political correctness, "Custer [has become] the symbol for all the inequities perpetrated by whites on Indians and some that were not." Favorite interpretations created by revisionist historians during the late 1900s were conveyance of utter fear and mass panic by soldiers at the Little Bighorn, rampant vanity of Custer that dictated his every action as if he were madly possessed, and government Indian policy diabolical to the core. At one point, pandering revisionists even paralleled the 1868 Custer-led attack against Southern Cheyennes at the Washita River with the 1968 My Lai massacre in Vietnam! Unfortunately, these impressions still linger today, despite being dreadful perversions of fact. "From a symbol of courage and sacrifice in the winning of the West," writes historian Paul Hutton, "Custer's image was gradually altered into a symbol of the arrogance and brutality displayed in the white exploitation of the West." The truth is Custer was not the leading Indian killer—others, namely General George Crook and Colonel Nelson Miles, were responsible for considerably more deaths. In fact, Custer seemed to express an understanding and sympathy for the Indians. Two years prior to his death he wrote: "If I were an Indian, I often think I would greatly prefer to cast my lot among those of my people [who] adhered to the free open plains, rather than submit to the confined limits of a reservation...." When determining Custer's proper historical legacy, it is fundamental to remember that Custer was by profession a soldier, and as such, one of his ordered duties was to fight Indians. Although he liked soldiering and was good at it, Custer did not make government policy. Moreover, Custer is widely criticized for his actions and subsequent defeat at the Little Bighorn. It seems Custer can not get a fair shake. Historian Stephen Ambrose issues this caution to students who want to separate the actual Custer of history from the Custer molded by legend and hearsay and political correctness: "More nonsense has been said, written, and believed about him than any other Army officer." What is the appropriate picture of Custer, according to solid historical evidence? Custer was the great-grandson of a Hessian officer (Küster) who had remained in America after the Revolutionary War. Upon graduation from West Point, where he was ranked last in his class of 34 and earned a number of demerits in the process, Custer entered the Civil War as a first lieutenant. He immediately distinguished himself at First Bull Run by single-handedly capturing six Confederates and their flag. Custer fought in every battle of the Army of the Potomac—he was especially conspicuous at Gettysburg and the Wilderness—garnering praise from his superiors, respect from his men, and accolades from his Confederate foes. Just two years into the war, at the young age of 23, Custer was promoted to the rank of brigadier general, and by the war's end had become a major general. The "Boy General" was a favorite of General Philip Sheridan, commander of the Union cavalry. At Appomattox, Sheridan presented Custer with the Confederate flag of truce, and gave Custer's wife, Elizabeth, the table on which General Robert E. Lee signed the articles surrendering his Army of Northern Virginia. Sheridan supplemented his gift to Mrs. Custer with firm compliments regarding the gallantry of her husband. After the war, Custer was dropped to the rank of captain, for like many officers in the Union Army, his wartime generalship was merely a brevet rank. Within a year, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and assigned to the 7th Cavalry out of Fort Riley, Kansas. Technically, Custer was second-in-command, but the regiment's colonel always seemed to be off somewhere, leaving Custer as the effective commander. Custer patrolled the Kansas grasslands and Oklahoma plains until his transfer to Fort Abraham Lincoln in Dakota Territory in 1873. The most notable incident during Custer's years in Kansas, and the genesis for all the Custer controversy, is the Washita River raid of December 1868. The historical distortions of the event and its aftermath are numerous. Chief Black Kettle's Cheyennes have been portrayed as thoroughly peace-loving yet specially targeted by the government to be brutalized. Custer's attack has been depicted as a maniacal rampage during which women and children were mercilessly slaughtered. Custer has been accused of abandoning outright one column of soldiers in the heat of battle (all 19 of which were killed by Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Kiowa warriors camped further down the Washita River coming to reinforce Black Kettle). Allegedly, one of the female prisoners taken by the soldiers was soon impregnated by Custer, resulting in a boy. Despite the fact that all these claims, popularized by Custer critics (and Indian lore to some degree), are considered either misleading, exaggerated, or downright false by reputable historians, the illusions remain part of Custer's legacy. If not a particularly handsome man, Custer was a stunning figure. He had bright yellow hair that hung in curls to his shoulders and vivid blue eyes. He stood just under six feet tall. Custer fashioned his own military attire—more flashy than the standard officer's uniform—and carried a sword of a Confederate soldier he shot during the Civil War. His favorite military action, demonstrated often, was to charge, regardless of the odds. Custer's "superabundance of courage" (Sheridan's phrase) is illuminated by his speedy ascent from lieutenant to general, for valor during the Civil War was recognized more commonly by award of rank than medals. Though he lost some horses beneath him, it was "Custer's luck" that he was never wounded. Custer possessed much energy and fully expected company around him to keep up with his hurried pace. It was not unusual for Custer to mount a fresh horse, after a long day of marching his troops, to hunt game or scout the trail ahead. It was this high level of energy, combined with his arrogance, courage, and passion, that made him somewhat of a dangerous leader. The 7th reflected the personality of its commander in two ways—the regiment became known not only for its superb horsemanship, but high desertion rate, as well (over 500 soldiers deserted in one year alone). Terry's departure from Fort Abraham Lincoln initiated the three-pronged assault aimed at forcing the Fort Laramie Treaty Indians back to their designated reservations. Terry's column and two other forces, under General George Crook (advancing northward from Fort Fetterman in Wyoming) and Colonel John Gibbon (coming from Fort Ellis in western Montana), would converge on the hostiles. Nearing the Indian encampment, having already rendezvoused with Gibbon, Terry sent Custer ahead with orders to proceed to the headwaters of Rosebud Creek so as to block the Indians' probable escape route. Once in place, Custer was to wait for the other columns to initiate the attack. (Several days earlier, unbeknownst to Terry and Custer, Crook's force had been halted by Crazy Horse at the Battle of the Rosebud.) As Custer and the 7th rode off to destiny, Gibbon admonished Custer, "Now, don't be greedy, Custer, as there are Indians enough for all of us. Wait for us." Custer replied, simply, "No, I won't." Was there an intentional double meaning in Custer's words? Did Custer promise that he would not attack prematurely or did he boldly assert that he would not wait for the other troops? The puzzling response set the stage for what was to come. Trailing along the Rosebud, Custer proceeded at an intense pace, covering almost 60 miles of difficult terrain in just two days. Instead of swinging well to the south and then doubling back to block the Indians' escape, as instructed, Custer turned his march almost directly toward the massive Indian encampment. It appeared he was making ready to attack the Indians with Terry and Gibbon still far off! On the morning of June 25 (the Terry/Gibbon forces were expected the next day), Custer divided his already grossly outnumbered command. He dispatched Major Marcus Reno with three companies to cross the Little Bighorn and attack the Indian village from the south. Captain Frederick Benteen was assigned three companies and given vague orders to sweep the bluffs southeast of the valley. One company, under Captain Thomas McDougall, stayed to guard the vulnerable pack train. Custer and the five remaining companies would engage the Indian encampment from the northeast. The formidable Indian alliance, numbering at least 2,000 strong (some estimates go as high as twice that amount) was led by Crazy Horse, the preeminent Sioux warrior chief, and Sitting Bull, spiritual emissary of the Sioux. Other notables present were Gall and Rains In The Face, both courageous Sioux chiefs, and Two Moons, a daring Cheyenne leader.

Custer's decision was disastrous. The mighty Indian army took less than an hour to obliterate Custer's much smaller main force of barely over 200. The reputed sole survivor was Captain Myles Keogh's horse, Comanche. Among the battle casualties were four relatives of Custer—two brothers, a brother-in-law, and a nephew. The nephew and one of the brothers had accompanied the expedition as civilians. The soldiers were later found naked, scalped, and mutilated. It is practically impossible to know with any precision the total Indian losses because they removed their dead from the field prior to fleeing the Little Bighorn region in the face of the approaching forces of Terry and Gibbon. Perhaps the best guess is between 50 and 100; one Indian-based source places the precise number at a scant 32 while some historians feel the correct number is well over 100. Sheer logic would suggest the true amount is closer to the latter offering. It is difficult to believe, given the battle's relatively open stage, that each of the dead 7th could not have taken down, on average, one enemy before themselves being killed. Custer died with bullet wounds in his heart and left temple, either of which would have been immediately fatal. Since his chest was very bloody and his head not, the logical conclusion is that the body wound was the first and fatal one and the shot in the head was meant as insurance. Some accounts describe Custer with an additional bullet hole in his right forearm, thought to have been an exit wound. Experts think Custer was probably shot from a distance, therefore lending support to the suggestion by a few historians that Custer died earlier in the battle (and was transported to the spot he was found dead) rather than the common perception that he was killed at close range as Indians closed in around the last desperate handful of soldiers bunched on Last Stand Hill. Some Indian narratives identify Custer's killer to be a young nephew of Sitting Bull named White Bull. Maybe so. How likely is it that one Indian inflicted both deadly wounds to Custer? Assuming the improbability that one warrior was responsible for Custer's two wounds, did the deadly shot come from White Bull or from the rifle of another Indian? In the pitch of battle, firing randomly from a distance into soldiers closely grouped, is it reasonable to suppose the shooter could detect exactly the enemy his bullet hits? Indians stated afterward that their eyes could not penetrate the dense clouds of dust and gun smoke, thereby limiting visibility to no more than ten feet (Indians killed Indians because of this). White Bull's staunch claim to have brought down Custer is based largely on the warrior's post-battle recollection that he shot a soldier wearing a buckskin jacket who was obviously one of the bluecoats' leaders. That White Bull killed a buckskin-clad foe that day is not in doubt. However, it is known that several other key officers besides Custer were wearing buckskin during the fight. Is it conceivable that after the battle White Bull and his comrades could have walked among the slain soldiers and, with any degree of consensus, pointed out those enemy they each killed? In 1909, the Indians themselves resolved the matter once and for all. By council it was decided to bestow the title of Custer's killer on Black Bear, a Southern Cheyenne chief whose résumé included encounters with Custer prior to the Little Bighorn. The fact that Custer's five companies struck the portion of the village inhabited by Cheyenne rather than Sioux slightly increases the odds of Custer's killer being of the former tribe and not the latter. Too much chaos, too many variables—several braves, including White Bull and Black Bear, could have accomplished the deed. Reportedly, Custer's corpse was naked but not subjected to extensive mutilation. The postmortem abuse was limited to punctured ear drums and a severed finger tip. Apparently, some Cheyenne women jabbed sticks into his ears so Custer would hear more clearly in his next life the warning of destruction, issued years earlier by a Cheyenne chief, if Custer ever made war on the tribe. There is no plausible reason for the missing bit of finger except sheer sport. It is uncertain why Custer's body was not severely ravaged. None of the several explanations offered has been universally accepted among historians. The most common story is that Custer's body was largely untouched as a gesture of extreme respect the Sioux had for their great enemy, but this might be nothing more than a tale of white origin intended to soothe damaged egos. Of the soldiers near Custer, some had been enthusiastically dismembered while others not. With such a lack of pattern, why would one presume that Custer's body was singularly spared while the others were just passed by? Any explanation based on the "honored enemy" premise relies on an unlikely scenario. When the last soldiers fall, the Indian warriors already at the scene immediately begin their frenzied ritual of victory-induced butchery. As the Indians jump from body to body amidst the crowded carnage of Last Stand Hill, the particular brave who first comes across Custer's corpse coincidentally recognizes him as the Indians' great enemy, whereupon the Indians nearby suddenly conjur enough emotional composure to decide, then and there, that the corspe should be spared mutilation owing to Custer's status as an honored adversary (well, except perhaps a souvenir finger tip). The sequence is doubtful at best. Even Cheyenne and Sioux narratives attest that the Indians did not know of their famous victim until later. The logical conclusion appears to be mere chance—some soldiers were extensively mutilated while some were not, and Custer just happens to fit in the latter category. As for Indians who would later support that Custer was indeed spared laceration as homage, it was not unusual for Indians to tell the version of a story they believed the white man wanted to hear, wary of reprisals if they did not. No doubt some Indians enjoyed the attention they received bending the ear of anxious listeners, so it is not unthinkable that the Indians might adjust the facts to accommodate the audience. Of course, the possibility exists that the reports of his body intact might have been fabricated, at least to some degree. There would be two reasons for doing this—to respectfully shield Mrs. Custer from graphic details of her disemboweled husband (and the haunting mental images that would probably prevail throughout her life) and to lessen, however slightly, America's psychological shock from the utter eradication of a hitherto invinsible national icon. Indeed, Lieutenant Edward S. Godfrey, one of the first soldiers to observe Custer dead, described him mildly: "His position was natural and one that we had seen hundreds of times while [he was] taking cat naps during halts in the march." Godfrey's choice of words gives the impression that the Indians had practically nothing to do with Custer's demise and that his death came as nonchalantly as an afternoon siesta after morning chores! It seems Custer might have disobeyed the orders of his superior by attacking the Indians alone. Some experts argue Terry's orders were quite specific—Custer was to remain in position until the additional forces arrived. Other authorities contend Terry had tacitly allowed Custer some freedom of decision based on whether Indian movements were observed by Custer's scouts. The orders were, in fact, ambiguous. While Terry expressed to Custer "his own views of what your action should be," Terry allowed that it was "impossible to give you any definite instructions in regard to this movement, and...places...too much confidence in your zeal, energy and ability to...impose upon you precise orders which might hamper your action when nearly in contact with the enemy." Nevertheless, two months after the battle, Terry stated that if Custer had survived he would have been court-martialed for disobedience. Grant echoed Terry, telling a New York Herald reporter: "I regard Custer's massacre as a sacrifice of troops, brought on by Custer himself, that was wholly unnecessary. He was not to have made the attack before effecting the junction with Terry and Gibbon." Was such criticism of Custer justified or was he made a scapegoat? Suffice to say the harsh remarks were not surprising—both Terry and Grant had ulterior motives for condemning Custer. Custer's defeat did not bode well for Terry's overall performance as commander; Grant's statement was equally predictable from a political standpoint. Grant was not fond of Custer for several reasons. On one occasion during the 1874 Black Hills expedition, Custer had Grant's son, Colonel Frederick Grant, arrested for drunkenness. Since, Custer had become critical of the government's peace policy toward the Indians, recently offering unflattering testimony before Congress concerning mismanagement of reservation agencies by Secretary of War William Belknap, and in doing so implicated the President's brother, Orville, of wrongdoing. On top of all that, certainly Grant, sensing public pressure bearing down on his tumultuous administration, heard Custer's name tossed about as a possible Democratic challenger to a third White House term, which Grant wanted. Regardless, Custer was not the only officer who disobeyed orders that day. Both of his immediate subordinates, Benteen and Reno, commanding the two columns earlier separated from the regiment, were also guilty of breaking orders. Just prior to engaging the Indians, Custer had summoned Benteen to return posthaste as reinforcement. Tragically, Benteen ignored the order, for reasons still unknown. He later blamed his slow response on the soldier who delivered Custer's order, an immigrant Italian private, Giovanni Martini, who spoke broken English. Apparently, when Benteen asked Martini to explain what was going on, the courier's limited response included only two distinguishable words, "Indians" and "skedaddling," which led Benteen to translate that Custer had the Indians on the run. Benteen's story, however plausible, and Martini's explanation, however muddied, still did not change Custer's written order, which certainly seems crystal clear no matter how it is read: "Benteen. Come on. Big village—be quick—bring packs." As for Reno, he was a West Point graduate twice decorated for gallantry in the Civil War. But now he was fighting quite a different enemy—not Confederate soldiers, but Sioux and Cheyenne warriors. In fact, the Little Bighorn was Reno's first battle against Indians. His performance was shoddy, at best. Reno had been ordered to attack the Indian village from the south. Some accounts indicate Reno's advancing column had the Indians at bay until the major strangely ordered his troops to halt and form a skirmish line, instantaneously shifting the military advantage from the charging cavalry to the Indian force. At this point, Reno is technically guilty of disobeying Custer's orders. If nothing else, he exercised poor judgment. A cavalry loses much of its effectiveness when it goes on the defensive, precisely what Reno did by forming skirmish lines. Additionally, instead of fending the surprise cavalry charge, the disconcerted Indians were allowed time to organize and mount a counterattack. In the opinion of some military experts, Reno's actions did not give Custer sufficient time to develop his portion of the assault. Reno's troops eventually withdrew into a stand of cottonwoods beside the river, where Reno sought advice from Custer's favorite Indian scout, Bloody Knife. As they peered from behind intermittent cover, a bullet suddenly shattered Bloody Knife's skull. His brains splattered on Reno's face. Already confused, Reno became especially anxious, at one point ordering his men to mount and then dismount three times in a matter of minutes. Any semblance of an orderly withdrawal now turned into a rout, with Reno leading the way backwards. The major climbed onto his horse and shouted to his troops, "Any of you men who wish to make your escape, follow me!" Thereupon he galloped off, leaving behind wounded soldiers as well as those too shaken to act with reason. What survived of Reno's command assembled on a nearby bluff and formed a defensive stance. There, a company surgeon inquired of Reno about the mad scramble. Reno curtly replied, "That was a charge, sir." Clearly, Reno and rationality had separated at some point between when Custer sent him forward and this moment. After pondering the orders delivered by Martini, Benteen had indeed started toward Custer, but at a gingerly pace. En route, he came upon Reno's decimated bunch. Reno dashed out and waved to Benteen, imploring him to stay on the bluff. Benteen did so, which effectively assured Custer and his troops of death, if they hadn't already perished. Notwithstanding Reno's higher rank, Benteen assumed command of the entire force on the hill, trapsing back and forth among the soldiers offering words of encouragement, all the time exposing himself to occasional Indian gunfire. Whatever can be said about Benteen, he was fearlessly cool under enemy fire. Confusion and indecision set in. The minds of Reno and Benteen must have been racing with unanswerable questions: Where is Custer?…Should we ride as reinforcements for him?…Is he even still alive?…How many Indians are really out there? For the two officers, all their questions meant just one thing—they would stay put. Thus, self-preservation had superceded the classic military rule-of-thumb that when in doubt or in absence of orders, move toward the sound of firing. A junior officer forced the matter. Against Benteen's wishes, Captain Thomas Weir (a devout Custer disciple) and a few others dutifully rode off toward Custer. Weir reached a high point where he could see only dust and Indians milling about. Meanwhile, the rest of the Reno/Benteen command joined Weir. They could get no closer to Custer. Indians spotted them and gave chase back to Reno's bluff, where a three-hour seige ensued, lasting until nightfall. Throughout the night, while the fighting slackened, the weary soldiers feverishly dug shallow trenches with makeshift tools—knives, forks, tin cups, whatever implements could move some dirt. The attack resumed the next morning and continued past noon. Then, during the early evening, the Indians unexpectedly struck camp. Just like that, the Little Bighorn fighting ended. It was here that Terry and Gibbon, the next day, caught up to what was left of Custer's decimated 7th Cavalry. The poor performance of Reno and the puzzling actions of Benteen are continuous topics of scholarly opinion. At Reno's own request, a Court of Inquiry was convened a couple years following the battle. After almost a month, and some 1,300 pages of intriguing testimony, the Court exonerated Reno, concluding that "there is nothing in his conduct with requires animadversion from this Court." In spite of the favorable verdict, Reno remained haunted the rest of his life by accusations of cowardice. Another army-related charge—he was accused of ordering a subordinate officer away on a mission, then using the absence as opportunity to make advances toward the officer's wife—further dampened his reputation. For this indiscretion, add drunkenness as well, Reno was dismissed from the Army in 1880. He died a bitter man in 1889. His gravesite is at the Little Bighorn cemetery. Benteen's behavior was questionable, but not irrational. A curious footnote adds to the mystery of his dawdling response to Custer's order—Benteen utterly despised Custer, and many people knew it because of some public verbal altercations between the two officers. Did Benteen linger, at least partially, owing to his contempt for Custer? It is a creepy thought and therefore tempting to make it part of the whole cloudy story of Custer's demise. But also it is highly doubtful. Benteen was a good military man, by all accounts above any vile character flaws which would cause him to let personal friction affect his loyal soldiering. In contrast to Reno, Benteen's private life and professional career took no post-Custer plunge. Two of Benteen's constants before the Little Bighorn, fighting Indians and criticizing the military prowess of Custer, continued after the dust had settled on Last Stand Hill, Medicine Tail Coulee, Weir Point, and Reno Hill. He retired as a brigadier general in 1888 and passed away a decade later. Custer's lopsided defeat was due to a combination of circumstances, still debated today by historians. His underestimation or disregard, whatever the true case may be, of the Indian strength was certainly a factor. Apparently, scouts had warned Custer of the enormous Indian force assembled at the Little Bighorn. In spite of this knowledge, Custer decided to split his already vastly outnumbered troops, which was a blatant error in military tactics. (Did Custer think back, once the instant arrived when he realized his fate, on his rejection of Terry's offer to send an additional 300-plus troops of the 2nd Cavalry along with the 7th?) Nevertheless, Custer's overconfidence was partially a product of his past experience—more than once, he had defeated a large Indian force with a surprise attack by his light and mobile cavalry. And almost certainly, had Reno and Benteen acted appropriately, the battle would have played out much differently. (Did Custer wonder, at the moment of truth, where were Reno and Benteen?) Though some experts feel that Custer, even with reinforcement from Reno or Benteen, would have been ultimately defeated because of his failure to gain the high ground, a crucial military objective in any engagement, perhaps complete annihilation could have been avoided. Of course, any prediction regarding the battle survival of Custer himself is pure speculation. Private William Taylor, a Little Bighorn veteran, wrote in 1910: "Reno proved his incompetence and Benteen showed his indifference—I will not use the words I've often thought about. Both failed Custer and he had to fight it alone." Did Custer initiate the attack out of perceived military necessity? Custer's decision to proceed without waiting for the Terry/Gibbon and Crook forces was based on Custer's mistaken belief that he had been detected by the Indians. If true, the Indians would quickly disperse and the entire campaign would dissolve. Custer's mission was to keep the Indians in place, so to allow escape without offering resistance would mean pure and simple failure, and that was not part of the Custer vernacular. According to Robert Utley, considered one of the foremost authorities on the battle, when each decision point is carefully analyzed, based on what Custer expected from his senior officers, coupled with what he had learned from past encounters with the Indians, "one is hard pressed to say what he ought to have done differently." Did Custer's luck simply run out? Maybe so. Utley again: "Custer died the victim less of bad judgment than of bad luck." Custer's contemporary and one of the most successful Indian fighters in history, General Nelson Miles, studied the battle and wrote in 1877: "The more I study the moves [at the Little Bighorn battlefield], the more I have admiration for Custer." Maybe Custer's selfish desire to have for himself the glory of the anticipated victory over the Indians impeded sound judgment. It has been suggested that Custer had mild aspirations of becoming President in 1876. The Republican Party was under scutiny because of the scandalous administration of Grant, which might open the White House door just enough to allow the Democrats to slip in. As a Democratic Party candidate opposed to the Reconstruction policies of the Republicans, Custer would attract votes from the South, while his successful Civil War record would be popular in the North. Moreover, Custer's courageous Indian campaigns would be very appealing to people not just in the West, but to all voters, who would be looking for a strong candidate—perhaps a military hero fresh from a resounding triumph over the menacing Plains Indians! It would not have been the first time an American public regarded the military battlefield as a presidential political campaign. The pressing need to determine a scapegoat for the Little Bighorn outcome does not seem to dwindle with time. Just about every important officer involved—even Gibbon, Terry, and Crook, none of whom were present at the battlefield on June 25, 1876—has at one time or another been criticized for actions contributing to the Army's defeat at the Little Bighorn. Custer, of course, has been saddled with most of the fault. His name has even become loosely synonymous with any one-sided disaster, military or otherwise. However, to believe that battlefield defeat always translates from blunderous officers or inadequate soldiers is flawed reasoning. Credit the Indian alliance for competent leadership and a hardy fight, as Robert Utley explains: "The simplest answer [to Custer's defeat], usually overlooked, is that the Army lost largely because the Indians won. To ascribe defeat entirely to military failings is to devalue Indian strength and leadership." Meanwhile, thousands of miles away, most of the country was immersed in summer-long festivities celebrating America's centennial. When the startling news of the Little Bighorn massacre and Custer's death reached eastern newspapers over the Fourth of July weekend, the federal government was humiliated (its grand campaign against the Plains Indians was foiled) and the public was shocked (army deaths at the hands of Indians was nothing new, but for Custer himself to have perished was beyond all comprehension). A giant Plains thunderstorm had rained on America's biggest party of the century! Almost overnight, Custer was transformed into a national martyr by numerous artists, authors, journalists, poets, and playwrights. Thus the beginning of Custer's historical rollercoaster. No figure in American history, with the possible exception of Christopher Columbus, has taken such a dive from exalted martyrdom to equally distorted depths of villainy as drastically as Custer. Ironically, the Indians' great victory at the Little Bighorn was their last stand, too. It alienated many of their white sympathizers in the East and moreover, the government became bent on avenging Custer's demise. Within just a few months, the Indians had surrendered to newly-organized forces under Terry, Crook, and others. They were returned to their reservations and forced to sign documents relinquishing the Black Hills to the United States. At that time, for all practical purposes, the Plains Indian Wars became history. Even at 23 years of age, the "Boy General" was not the youngest Civil War general. That distinction goes to Galusha Pennypacker of Pennsylvania, who achieved his exalted rank at age 20. He remains the youngest general in American military annals to date; chances are good he will forever hold that recognition. Incidentally, Pennypacker's Confederate counterpart was William P. Roberts from North Carolina who (like Custer) was a brigadier general by age 23. George and Libbie Custer were recognized by others as a playful and laughing couple. George preferred to sit next to Libbie, rather than across, when dining together. When apart from his wife, Custer sent her immense flowing letters almost every night, on one occasion writing 80 pages in a single sitting! He once abandoned his Kansas regiment (not during battle) to ride through the night to be with her—a gallant but irresponsible act. Connell describes their relationship thusly: "Custer was the knight sans peur et sans reproche, while she was his lady fair." Custer was flirtatious enough with other women, but there's nothing substantial to indicate that he ever went beyond that. Libbie is buried next to her husband at West Point Military Academy in New York. In lieu of children, of which Custer fathered none, he directed his affection toward animals (horses and dogs being his favorites). Custer's pack of dogs, which he spoiled outrageously, were often seen cuddled with him as he napped. He kept a pet mouse in the empty inkwell on his desk, sometimes extending his finger to allow the creature to scurry up his arm and run playfully through his hair. Custer even took a pelican from the Arkansas River for a pet, sometimes hauling it along as his Fort Riley regiment patrolled the dusty Kansas plains! Did the two archenemies of the Little Bighorn saga—Crazy Horse and Custer—actually see each other during the battle? It is not out of the question that they did, if even just a momentary glance. In fact, they might have been within just 20 yards of one another at some point. But the odds that they recognized one another are slim. Custer had never before laid eyes on Crazy Horse, so the face of Crazy Horse would not have aroused Custer's memory. Indian sources stated that although they surmized the soldiers were led by a great leader, they did not know, during the course of the fighting, that it was Custer. Certainly, there was no duel-like stare down between the two combatants during some surreal five-second lull in the battle. Comanche, the alleged sole survivor of Custer's immediate command at the Little Bighorn massacre, emerged from battle with severe wounds from arrows and bullets. Other mounts lived through the fight, but were so hopelessly wounded that they had to be destroyed. Certainly any untouched horses were taken by Indians. Comanche was nursed back to health at Fort Abraham Lincoln and lived another 15 years. The gelding died in 1891 at Fort Riley, was stuffed, and is currently displayed at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. Failure to account for all the soldiers' bodies immediately after the fight left the faint possibility that one or two troopers somehow escaped death. Of the plenty "only survivor" tales—there were "more claimants than Custer had soldiers" writes historian Evan Connell—the one given most attention by historians is that of Pvt. Nathan Short of Company C, one of three companies massacred on Custer Hill. Five weeks after the battle, soldiers under Gen. Terry's command happened upon a dead cavalry horse on the lower Rosebud River, some 70 miles northeast of the Little Bighorn battlefield. The horse was shot between the eyes. Most of its government-issue equipment was intact (the only key item missing was the bridle). Ten feet from the carcass lay a carbine in good condition. Less than a week later, the body of a cavalry trooper was discovered upstream a few miles. Careful inspection of his gear seemed to indicate that he was a member of Custer's 7th. The hat was of new design that so far had been issued only to the 7th. Drawn on the hat was "7C" which was key for two reasons—its apparent confirmation that the hat belonged to one of the 7th's Company C soldiers, and more importantly, because several battle survivors specifically associated the personal etching with Short, recalling that his company sergeants were displeased that he marked his hat. Additionally, the initials "N.S." were on the inside of the dead soldier's cartridge belt. According to Curley, one of Custer's Crow scouts, Custer paused momentarily in Medicine Tail Coulee just moments prior to battle. There, he summoned a trooper and after a brief conversation, the soldier (presumably Short) headed north toward Terry. Yet, based on interviews with surviving members of Custer's 7th, Short was known to have been in the ranks on June 25 when the attack commenced. Curley's entire recollection is somewhat perplexing because of what he did not include. If Curley did indeed witness a messenger sent, it could have been Sgt. Daniel Kanipe, sent to McDougall with instructions regarding the pack train, or Pvt. Martini, urgently dispatched to bring Capt. Benteen into battle. But both of these riders would have headed in the opposite direction that Curley claimed his lone soldier galloped. Additionally, Curley did not seem to recall two riders, let alone three—there is no question that Custer dispatched both Kanipe and Martini (so Curley's alleged rider would have totaled three sent by Custer). How is it that Curley could recall one rider (aka Short) but not two others (aka Kanipe and Martini)? There should have been no trouble recalling such information because Custer released Curley and the other Crow scouts after he sent Kanipe and Martini on their ways. If the mysterious corpse was in fact that of Short, then the debate arises as to whether he was courier or defecter. Would a deserter flee in the direction of Terry's command, thus risking interception? Either way, Short technically can not be classified as a survivor at all, since he departed before the actual fighting commenced. On the other hand, he is the only member of the three annihilated companies under Custer to live beyond June 25. In 1886, ranchers buried in the vicinity what many think are the remains of Short. Today a bronze plaque embedded in a large stone, placed in 1983, briefly tells the story. The Nathan Short Monument is located on Highway 477, six miles south of the Rosebud exit off Interstate 94. Short's name also appears on the Custer Monument as officially killed in action. Crazy Horse was killed a year after the Little Bighorn fight while imprisoned at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. He was stabbed by a soldier who apparently thought he was trying to escape from jail. Sitting Bull fled to Canada, where he remained until finally surrendering in 1881. After that, he toured the country for several years with Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show. Sitting Bull was later shot by soldiers attempting to arrest him in 1890 at the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota, prefacing the unfortunate Wounded Knee incident, considered the culminating event of the Plains Indian Wars in American history. The lively tune associated with Custer's 7th is "Garry Owen," an Irish drinking song dating back to about 1800. Its verses are of street brawls, shattering windows, chasing the sheriff, and similar activities provocated by too much liquor intake. It was probably Capt. Keogh who proposed that the 7th have its own band and suggested the catchy quick-step as the regimental marching song. Custer approved, personally donating $50 toward the cost of the band's instruments. "Garry Owen" was the last song played as Custer and his troops rode off toward the Little Bighorn. After reading the infamous message delivered by Pvt. Martini, Capt. Benteen tucked it into his pocket. For several years, the note was presumed to have been lost. It eventually surfaced, about 50 years later, in the hands of a New Jersey collector. It is now in the West Point library. Artists are seldom friends of historians and the Little Bighorn clash is no exception. In all, well over 1,000 pictures of the fight have been produced, the first of which was completed by William de la Montague Cary just two weeks after the earliest telegraphed reports revealed the unbelievable news! Over time, Indians who fought in the battle drew numerous accounts, as well. All of the renditions contain errors. Some paintings depict Custer with long hair. Actually, his hair was cut short prior to the battle. Other drawings portray Custer brandishing a saber. In truth, Custer was armed with two pistols (none of the 7th took their swords into battle that day). Additional prints show Custer mounted on his horse. He likely was afoot during most of the battle, but certainly in the waning minutes, if he lived that long. Still more versions have Custer wearing his Civil War uniform. In reality, he donned an outfit of his own design—blue flannel shirt, buckskin trousers, and a broad-rimmed hat. Experts today consider Eric von Schmidt's Here Fell Custer, painted in 1976, to be the most historically accurate painting. The National Park Service has endorsed the von Schmidt artwork as its "official" canvas interpretation of the battle. In the June 1976 issue of Smithsonian magazine, von Schmidt discussed his work. Instead of showing the battle from the traditional "naive, poster-like treatment" of the attacking Indians, von Schmidt uniquely sought to convey "a sense of what the troopers were experiencing as their individual deaths pressed in upon them." Viewers of Here Fell Custer can almost hear the "shrill blasts of eagle-bone whistles carried by most of the warriors, high-pitched war cries [and] shouts, the dull roar of horses' hooves, shrieks of wounded men and horses, the rattle of gunfire, and the ceaseless deadly whirr of arrows—a dissonant cacophony of death." The most famous of all the earlier Last Stand paintings is E. Otto Becker's 1895 lithograph Custer's Last Fight, derived from a decade-old original painting by Civil War veteran Cassilly Adams. The Adams painting measured 9½ by 6½ feet; Becker reduced it and apparently modified it somewhat. According to von Schmidt, the Sioux and Cheyenne Alliance was transformed into the "Zulu Nation" when Becker added the "strange shields" among the fighting warriors. Becker's work was sent to 150,000 saloons courtesy of the Anheuser-Busch Company. Chances are that the millions of beer-guzzling Americans who gazed at it with blurred vision resulting from "diminishing sobriety" did not take issue with the Indians' weaponry or any other historical flaws. Until von Schmidt, the most regarded painting of the Little Bighorn battle was Custer's Last Stand, completed by Edgar Samuel Paxson in 1899. As his chief source, Paxson consulted General Godfrey, the Little Bighorn survivor (a lieutenant at the time) who was one of the first to happen upon the finished scene on Last Stand Hill and later returned as a member of the burial party. Paxson's piece did not particularly impress von Schmidt, who noted that it "...shows six identifiable officers and virtually every Indian leader in the fight, all miraculously converging in the same place at the same time." From the huge amount of literature about Custer and the Little Bighorn, three definitive books stand forth. Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors, by Stephen E. Ambrose, was published in 1975. Ambrose's impressive research produces thorough biographical accounts of the two adversarial Little Bighorn war leaders. The book reads smoothly and captivates. In preparation for his writing, Ambrose spent four years traveling and visiting Indian decendants of the Little Bighorn warriors in Montana, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming. Evan S. Connell's 1984 national bestseller, Son of the Morning Star: Custer and the Little Bighorn, is meticulously researched. The book reveals the complexity of the man Custer—the person and the professional—and vividly narrates the details of his last battle. Connell intertwines Custer, other military men, government officials, and Indian leaders as he skillfully slides back and forth from scene to scene in the entire Little Bighorn saga. Any student of American history is sure to find the book absolutely engrossing, for it meanders like a suspenseful novel rather than lectures like a mundane historical account. Connell's work served as the basis for a made-for-television movie of the same title. Unfortunately, the film deviated at times from Connell's version thus creating a product that hardly reflected the impeccable work of Connell. When it was first published in 1988, Cavalier in Buckskin: George Armstrong Custer and the Western Military Frontier, by Robert M. Utley, met with critical acclaim. The author provides a no-frills portrait of Custer. Utley maintains that the unbounded criticism piled on Custer for his famous defeat is unjustified: "Custer does not deserve the indictment that history has imposed upon him for his actions at the Little Bighorn." The author specifically opposes the thesis that Custer's decision to engage the Indians at the Little Bighorn was founded in a titanic desire for personal glory. Utley's scholarship is respected beyond question. He worked as historical aide for the National Park Service at the Custer Battlefield for several summers (1947-52). Curiously, in his book's newest edition, Utley mentions Son of the Morning Star, describing it as "a vast, rambling potpourri of Custeriana." However interpreted, the comment is hardly a ringing endorsement of Connell's work. Here's the bottom line. Ambrose, Connell, Utley—choose any one—will not disappoint. All three volumes are necessary scholarship for students of Custer, the Little Bighorn clash, and peripheral matter. If you desire even more, read Larry Sklenar's To Hell With Honor: Custer and the Little Bighorn, published in 2003. He takes the position that Custer could have succeeded had Reno and Benteen not betrayed him. Later during the summer of the Little Bighorn battle, luck ran out for another associate of Custer. One of his principal scouts from Civil War days, James Butler "Wild Bill" Hickok, was killed in Deadwood, Dakota Territory. He was shot from behind by Jack McCall while playing poker in Nuttall and Mann's No. 10 Saloon. On the night of August 1, McCall had played cards with Hickok and lost heavily. The next morning, Hickok insisted on lending McCall money for breakfast. Hickok's peace offering was not enough—McCall shot him that afternoon. The bullet entered Hickok's skull, emerged from his cheek, and lodged in the wrist of another card player at the table. The 39-year-old Hickok, a newcomer to Deadwood, had a reputation as a fast-draw gunslinger and inveterate gambler. Both were well deserved. When Hickok joined the table of card players that day, the only available chair forced him to sit, uncharacteristically, facing away from the saloon proper. He was an easy target for McCall, who had been drinking at the bar. According to story, at the moment he was murdered, Hickok held the aces and eights of clubs and spades. The identity of the other card in Hickok's hand is obscure. Numerous fifth cards have been proposed by various sources—the most commonly named are five, nine, jack, and queen of diamonds; queen of clubs; and king of spades. There is some reason to believe Hickok had reduced his hand to four cards through discard and that the shooting coincidentally occurred in the momentary interum before the draw, hence the historical uncertainty because some of the cards alleged to be the mysterious fifth could have been discards from other players' hands. The combination of black aces and eights (with any kicker) has been known ever since as the "dead man's hand." McCall fled the premises, but was immediately apprehended by a large group of townspeople. The murder was as cold-blooded as it gets, but nevertheless an informal court held in McDaniel's Theater failed to convict McCall. Apparently McCall could not keep his mouth shut about his infamous deed. After leaving Deadwood and heading west, he bragged himself into arrest in Laramie, Wyoming Territory. He was brought back to Dakota Territory where he was retried, found guilty, and hanged in Yankton, the territorial capital. McCall is the first person executed in Dakota Territory for a federal offense. Hickok is buried in Deadwood's Mount Moriah Cemetery along side Calamity Jane (nee Martha Jane Cannary), another Deadwood figure of curious repute, who posed as a man much of her life. She was, among other things, a sometimes prostitute who after Hickok's death claimed to be his widow (unquestionably, she was not). At his funeral, Jane tearfully pronounced Wild Bill's body "the purtiest corpse I ever saw." Incidentally, there is a No. 10 Saloon in Deadwood today, but its location differs from the legendary 1876 establishment. |